The final servicing mission to the venerable Hubble Space Telescope (HST) was in 2009. The shuttle Atlantis completed that mission (STS-125,) and several components were repaired and replaced, including the installation of improved batteries. The HST is expected to function until 2030 - 2040. With the retiring of the shuttle program in 2011, it looked like the Hubble mission was destined to play itself out.

But now there's talk of another servicing mission to the Hubble, to be performed by the Dream Chaser Space System.

A view of the Hubble Space Telescope from inside space shuttle Atlantis on mission STS-125 in 2009, the final repair mission. Credit: NASA

The servicing mission to the Hubble would be a sort of insurance policy in case there are problems with NASA's new flagship telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST.) The JWST is due to be launched in 2018, and its capabilities greatly exceed those of the Hubble. But the James Webb's destination is LaGrange Point 2 (L2), a stable point in space about 1.5 million km (932,000 miles) from Earth. It will enter a halo orbit around L2, which makes a repair mission difficult. Though deployment problems with the JWST could be corrected by visiting spacecraft, the Telescope itself is not designed to be repaired like the Hubble is.

Since the JWST is risky, both in terms of its position in space and its unproven deployment method, some type of insurance policy may be needed to ensure NASA has a powerful telescope operating in space. But without Space Shuttles to visit the Hubble and extend its life, a different vehicle would have to be tasked with any potential future servicing missions. Enter the Dream Chaser Space System (DCSS).

The Dream Chaser Space System is kind of a smaller Space Shuttle. It can carry seven people into Low-Earth Orbit (LEO). Like the Shuttles, it then returns to Earth and lands horizontally on an airstrip.

The HST has been called the most successful science project ever. Entire books have been written detailing its contributions to science. It would be a sad end for the Hubble if it was somehow rendered useless because of a simple-to-fix problem, yet stayed in orbit, just out of reach. Somehow, that doesn't seem right. Even though it was put into Low-Earth Orbit in 1990, it's still a powerful telescope that keeps delivering results. A back-up plan to keep Hubble running is smart.

The DCSS is built by Sierra Nevada Corporation. It will be launched on an Atlas V rocket, and will return to Earth by gliding, where it can land on any commercial runway. The DCSS has its own reaction control system for manoeuvering in space. Like other commercial space ventures, the development of the DCSS has been partly funded by NASA.

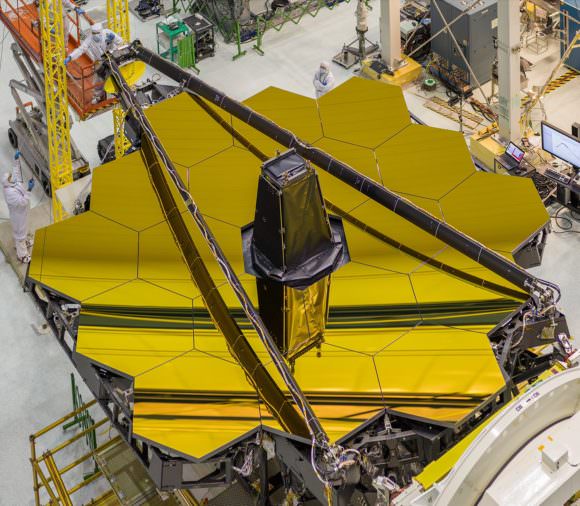

The primary mirror of the James Webb Space Telescope, in all its gleaming glory! Image: NASA/Chris Gunn

The James Webb has a complex deployment. It will be launched on an Ariane 5 rocket, where it will be folded up in order to fit. The primary mirror on the JWST is made up of 18 segments which must unfold in three sections for the telescope to function. The telescope's sun shield, which keeps the JWST cool, must also unfold after being deployed. Earlier in the mission, the Webb's solar array and antennae need to be deployed.

This video shows the deployment of the JWST. It reminds one of a giant insect going through metamorphosis.

If either the mirror, the sunshield, or any of the other unfolding mechanisms fail, then a costly and problematic mission will have to be planned to correct the deployment. If some other crucial part of the telescope fails, then it probably can't be repaired. NASA needs everything to go well.

People have been waiting for the JWST for a long time. It's had kind of a tortured path to get this far. We all have our fingers crossed that the mission succeeds. But if there are problems, it may be up to the Hubble to keep doing what it's always done: provide the kinds of science and stunning images that excites scientists and the rest of us about the Universe.

No comments:

Post a Comment